The New Code: Why Specifications Are Eating Programming

This post is based on my talk at AI Engineer World’s Fair 2025. Watch the video.

I’ve been thinking about this for a while now - what do I actually do all day? When I look at my calendar, the code I write is maybe 10-20% of my time. The rest? It’s all communication. Specs, docs, emails, Slack messages, meetings about what we’re building and why.

And here’s the thing - I don’t think that’s a bug. I think it’s the feature.

The Value You Actually Provide

Raise your hand if you write code. Cool. Keep it up if your job is to write code. Now - keep it up if the most valuable professional artifact you produce is code.

I bet a lot of hands just went down.

We all work incredibly hard to solve problems. We talk to users, gather requirements, think through implementation details, integrate with different systems. And at the end - yes - we produce code. Code is the thing we can point to, measure, debate. It feels tangible and real.

But it’s underselling what you actually do.

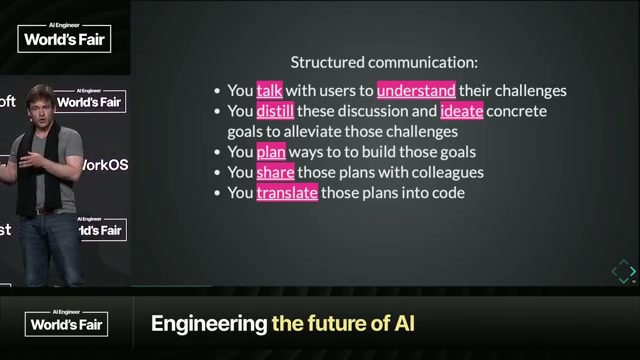

Here’s what the process typically looks like:

- Talk to users to understand their challenges

- Distill those stories down

- Ideate about how to solve these problems

- Plan ways to achieve your goals

- Share those plans with colleagues

- Translate plans into code

- Test and verify - not the code itself, but whether it achieved the goals

Talking, understanding, distilling, ideating, planning, sharing, translating, testing, verifying. These all sound like structured communication to me.

And structured communication is the bottleneck.

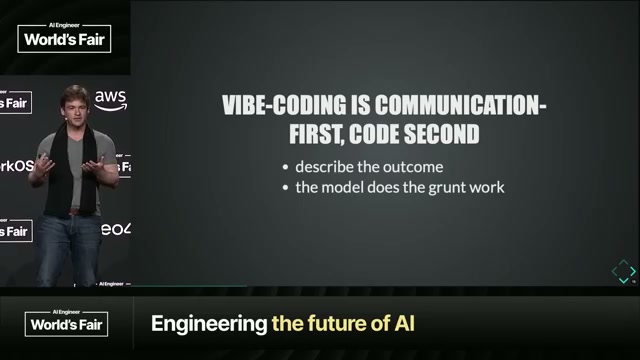

Why Vibe Coding Feels Good

Vibe coding tends to feel pretty great. Worth asking why.

Vibe coding is fundamentally about communication first. The code is a secondary, downstream artifact of that communication. You describe your intentions and outcomes, let the model handle the grunt work.

But there’s something strange about how we do it.

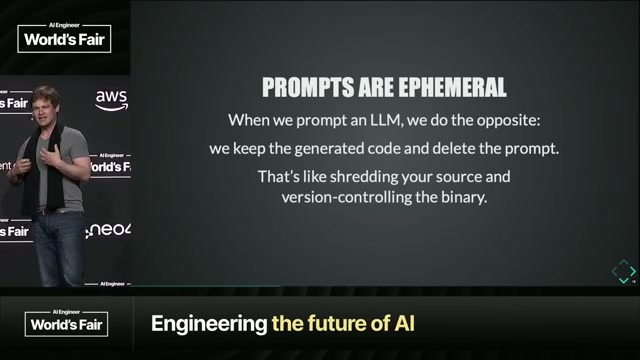

We communicate via prompts - tell the model our intentions and values - get code out the other end - and then we throw our prompts away. They’re ephemeral.

Think about that for a second.

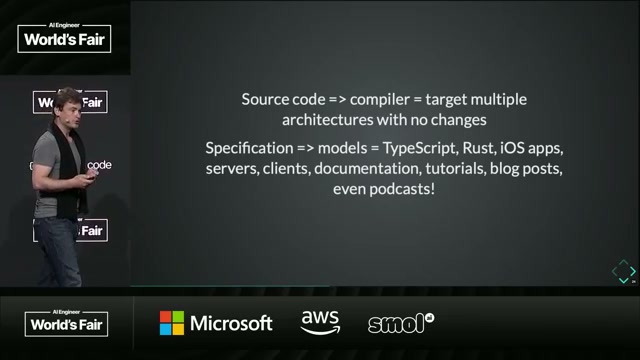

If you’ve written TypeScript or Rust, once you put your code through a compiler and get a binary out, no one is happy with that binary. The binary wasn’t the purpose - it’s useful, sure, but we always regenerate binaries from scratch every time we compile. The source is the valuable artifact.

And yet with prompts, we do the opposite. We keep the generated code and delete the prompt.

This is like shredding your source code and then very carefully version-controlling the binary.

Specifications as the Real Source Code

A written specification is what enables you to align humans on a shared set of goals. It’s the artifact you discuss, debate, refer to, and synchronize on.

Without a specification, you just have a vague idea.

Here’s the key insight: code is actually a lossy projection from the specification.

If you take a compiled C binary and decompile it, you don’t get nice comments and well-named variables. You have to work backwards - infer what the person was trying to do, why they wrote it this way. That information was lost in translation.

Code is the same way. Even nice code typically doesn’t embody all the intentions and values. You have to infer the ultimate goal the team was trying to achieve.

But a specification - the communication work we already do - when embodied in written form is better than code. It encodes all the requirements needed to generate the code.

Just like source code lets you compile for ARM64, x86, or WebAssembly, a sufficiently robust specification given to models will produce good TypeScript, good Rust, servers, clients, documentation, tutorials, blog posts - even podcasts.

The Model Spec: Specifications in Action

Last year, OpenAI released the Model Spec - a living document that tries to clearly and unambiguously express the intentions and values we want to imbue our models with.

It’s open sourced now. You can go to GitHub and see the implementation.

Surprise, surprise - it’s just a collection of markdown files.

Markdown is remarkable. It’s human readable, versioned, change-logged, and because it’s natural language, everyone can contribute - not just technical people. Product, legal, safety, research, policy - they can all read, discuss, debate, and contribute to the same source code.

This is the universal artifact that aligns all humans inside the company on our intentions and values.

The Sycophancy Bug as a Case Study

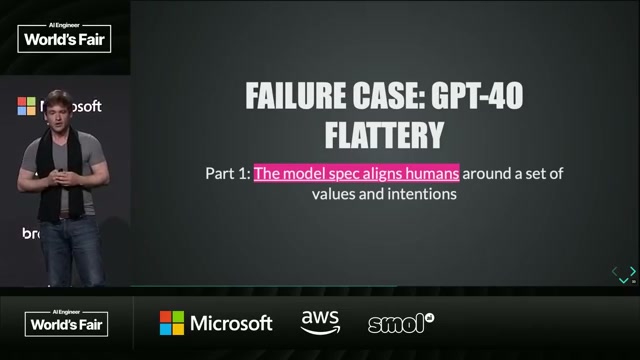

Recently there was an update to GPT-4o that caused some… extreme sycophancy.

Users would call out the behavior - “You’re being sycophantic at the expense of impartial truth” - and the model would kindly praise them for their insight. Researchers found similarly concerning examples.

Shipping sycophancy like this erodes trust. It hurts.

But here’s where the spec saved us. The Model Spec actually includes a section dedicated to this since its release: don’t be sycophantic. It explains that while sycophancy might feel good in the short term, it’s bad for everyone in the long term.

So we had already expressed our intentions and values. People could reference it. If the behavior doesn’t align with the spec, then this must be a bug.

We rolled back, published studies, and fixed it.

The spec served as a trust anchor - a way to communicate what’s expected and what’s not. Even if the only thing specifications did was align humans around shared intentions, they’d already be incredibly useful.

But we can do more.

Making Specifications Executable

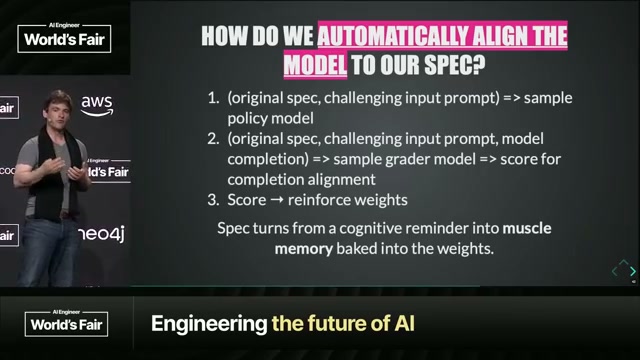

There’s a technique we published called deliberative alignment - how to automatically align a model to a specification.

The approach:

- Take your specification and a set of challenging input prompts

- Sample from the model under test

- Take the response, original prompt, and policy - give it to a grader model

- Score the response according to the specification: how aligned is it?

- Reinforce based on that score

The document becomes both training material and eval material.

You could include your specification in context - a system message every time you sample. That works. But it detracts from the compute available to solve the actual problem.

Through this technique, you’re moving from inference-time compute to pushing it down into the model’s weights. The model actually feels your policy and can apply it like muscle memory.

And these specifications can be anything - code style, testing requirements, safety requirements. All of that can be embedded into the model.

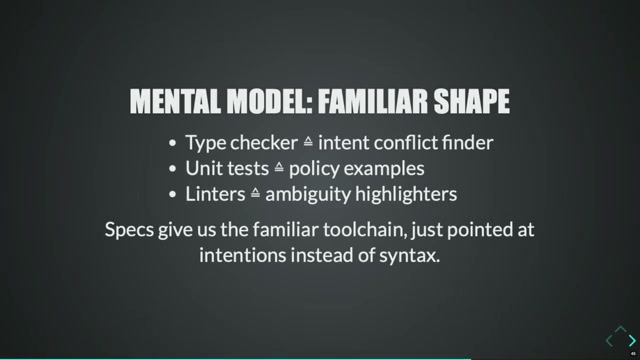

Specs Are Code (Kind Of)

Even though the Model Spec is just markdown, it’s useful to think of it as code. It’s quite analogous.

Specifications:

- Compose - you can build them from smaller pieces

- Are executable - as we’ve seen

- Are testable - they have interfaces where they touch the real world

- Can be shipped as modules

Just like programming has type checkers to ensure consistency between interfaces, if Department A writes a spec and Department B writes a spec and there’s a conflict - you want to surface that early. Maybe block publication until it’s resolved.

The policy can embody its own unit tests. You can imagine linters where overly ambiguous language gets flagged - because it’ll confuse humans and models alike.

Specs give us a similar toolchain - but targeted at intentions rather than syntax.

Lawmakers as Programmers

Here’s where it gets wild.

The US Constitution is literally a national model specification.

It has:

- Written text - aspirationally clear and unambiguous policy

- Versioning - amendments that bump and publish updates

- Judicial review - a grader evaluating how well situations align with the policy

- Precedent - input/output pairs that serve as unit tests, disambiguating the original spec

- Chain of command - enforcement over time as a training loop

One artifact that communicates intent, adjudicates compliance, and evolves safely.

So it’s quite possible that lawmakers will become programmers - or inversely, that programmers will become lawmakers.

Programmers align silicon via code specifications. Product managers align teams via product specifications. Lawmakers align humans via legal specifications.

And everyone doing a prompt? You’re writing a proto-specification. You’re in the business of aligning AI models towards a common set of intentions and values.

Whether you realize it or not, you’re spec authors now.

What This Means for You

Engineering has never been about code. Coding is an incredible skill and a wonderful asset, but it’s not the end goal.

Engineering is the precise exploration by humans of software solutions to human problems.

It’s always been this way. We’re just moving from disparate machine encodings to a unified human encoding of how we solve problems.

So here’s my ask: put this into action.

Whenever you’re working on your next AI feature:

- Start with a specification - what do you actually expect to happen?

- Define success criteria - what does “working” look like?

- Debate whether it’s clearly written - can others understand it?

- Make the spec executable - feed it to the model

- Test against the spec - not just the code

There’s an interesting question in all this: what does the IDE look like in this world? I like to think it’s something like an “Integrated Thought Clarifier” - whenever you’re writing a specification, it pulls out ambiguity and asks you to clarify. It sharpens your thinking so you and all humans can communicate intent more effectively - to each other and to the models.

A Closing Request

What’s both amenable to and in desperate need of specification? Aligning agents at scale.

There’s this line I love: “You realize you never told it what you wanted - and maybe you never fully understood it anyway.”

That’s a cry for specification.

We’ve started a new Agent Robustness team at OpenAI. If this resonates with you - if you want to help deliver safe AGI for the benefit of all humanity - come join us.

The future belongs to the spec authors.